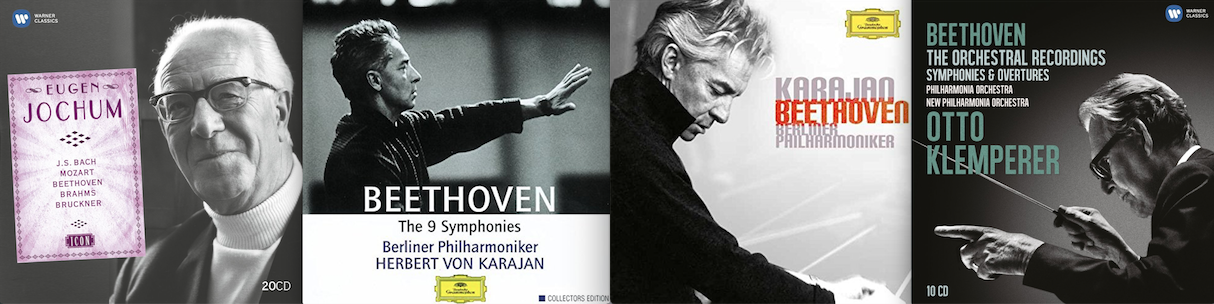

As with Otto Klemperer, I first encountered German conductor Franz Konwitschny when I explored the symphonic works of Anton Bruckner a year or two ago (see My Year-Long Project for details about my musical explorations, including Anton Bruckner).

As with Otto Klemperer, I first encountered German conductor Franz Konwitschny when I explored the symphonic works of Anton Bruckner a year or two ago (see My Year-Long Project for details about my musical explorations, including Anton Bruckner).

The orchestra for today’s recording is the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, the Wikipedia entry for which tells us this:

The Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra (Gewandhausorchester; also previously known in German as the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig) is a German symphony orchestra based in Leipzig, Germany. The orchestra is named after the concert hall in which it is based, the Gewandhaus (“Garment House”). In addition to its concert duties, the orchestra also performs frequently in the Thomaskirche and as the official opera orchestra of the Leipzig Opera.

The orchestra’s origins can be traced to 1743, when a society called the Grosses Concert began performing in private homes. In 1744 the Grosses Concert moved its concerts to the “Three Swans” Tavern. Their concerts continued at this venue for 36 years, until 1781. In 1780, because of complaints about concert conditions and audience behavior in the tavern, the mayor and city council of Leipzig offered to renovate one story of the Gewandhaus (the building used by textile merchants) for the orchestra’s use.

I find that interesting.

Speaking of interesting, here’s Konwitschny’s bio on Wikipedia:

Franz Konwitschny (August 14, 1901, Fulnek, Moravia – July 28, 1962, Belgrade) was a German conductor and violist.

He started his career on the viola, playing in the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra under Wilhelm Furtwängler. In 1925, he moved to Vienna, where he played the viola with the Fitzner Quartet. He also began teaching at the Wiener Volkskonservatorium. He later became a conductor, joining the Stuttgart Opera in 1927. From 1949 until his death he was principal conductor of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. From 1953 until 1955 he was also principal conductor of the Dresden Staatskapelle and from 1955 onward he led the Berlin State Opera.

Like Furtwängler, Konwitschny used “expansive gestures” and had a “dislike of an exact beat.” Konwitschny recorded a complete cycle of Beethoven symphonies.

He was given the nickname Kon-whisky because of his heavy drinking habits.

Konwitschny sounds like he was a character, which is the reason why I was pleased to see that he had conducted a cycle of Beethoven symphonies. I remember enjoying this character’s work with Bruckner. So I wanted to find out what he did with Beethoven.

Also, the history of the orchestra has “character” written all over it, too. Just look at this list of music directors who lead the orchestra over the years:

Mendelssohn? Furtwangler? Konwitschny? Masur? Blomstedt? Chailly?

I know Mendelssohn as a composer. I know the others as conductors in my Bruckner project. It’s a prestigious list of music directors.

All of this history and character combine this morning to give me high hopes for a magical listening experience in the world of Classical music.

All of this history and character combine this morning to give me high hopes for a magical listening experience in the world of Classical music.

And I’m not disappointed.

From the superb liner notes written by Matthias Hansen (“Franz Konwitschny and Beethoven’s symphony cycle: A brief history of the series”):

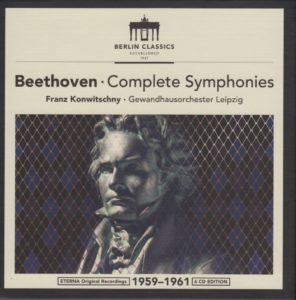

Beethoven’s nine symphonies are one of the fundamental building-blocks in the history of Western music. Under the direction of Franz Konwitschny they are were an early part of the recording and release programme at Eterna, where recordings of the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies with the Gewandhaus Orchestra appeared on several shellac discs each. This stereo edition of the complete cycle was made in co-production with Philips in the Bethanienkirche in Leipzig during three extended recording sessions over the period 1959-1961.

From the fascinating liner notes written by Werner Wolf (“The Beethoven tradition of the Leipzig Gewandhaus”):

During his 13-year tenure, Konwitschny presented three cycles of orchestral works by Beethoven, including all symphonies as well as selected overtures and concertos. Five Beethoven concerts in as many weeks were given under his baton in March and early April 1952 to mark the 125th anniversary of the composer’s death.

All those performances of Beethoven’s work, whether presented separately or as part of a cycle, were remarkable for a spontaneous but sophisticated style of playing far removed from any routine, academic suavity and shallow perfectionism. With his authoritative, flexible and impulsive but relatively sparse gestures, Konwitschny knew how to inspire the orchestra and respond to it.

Truly wonderful information. That’s the very reason for which liner notes were created.

Beethoven wrote his symphonies in four parts (except for the Sixth, which is in five). The time breakdown of this particular one (Symphony No. 1 in C Major), from this particular conductor (Kontwitschny, at age 58) and this particular orchestra (Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra), at this particular time in history (June 11-26, 1959) on this particular record label (Berlin Classics) is as follows:

I. Adagio molto………………………………………………………………………………..9:12

II. Andante cantabile con moto………………………………………………………8:16

III. Menuetto. Allegro molto e vivace……………………………………………….3:43

IV. Adagio – Allegro molto e vivace…………………………………………………5:31

Total running time: 26:30

My Rating:

Recording quality: 4 (for its age, this is excellent; very noticeable tape hiss notwithstanding)

Overall musicianship: 5

CD liner notes: 5 (two essays that contain exceptional historical and technical detail by Matthias Hansen and Werner Wolf)

How does this make me feel: 5

I didn’t expect much from this unassuming little box set of Beethoven symphonies conducted by Franz Konwitschny, from an era long past, on a label (Berlin Classics) I didn’t recognize. But I’ll be darned. This is a hidden gem of a release – at least based on Symphony No. 1 in C Major and the well-researched and -written liner notes. I can’t wait to hear the other symphonies in this set!

Today’s performance – as well as the overall feeling I get from reading the information, seeing the historical photos, and imagining these people playing their hearts out for the Maestro back in the latter 1950s – rates an unequivocal “Huzzah!”