Today, I have the legendary German conductor Wilhelm Furtwangler on tap.

Today, I have the legendary German conductor Wilhelm Furtwangler on tap.

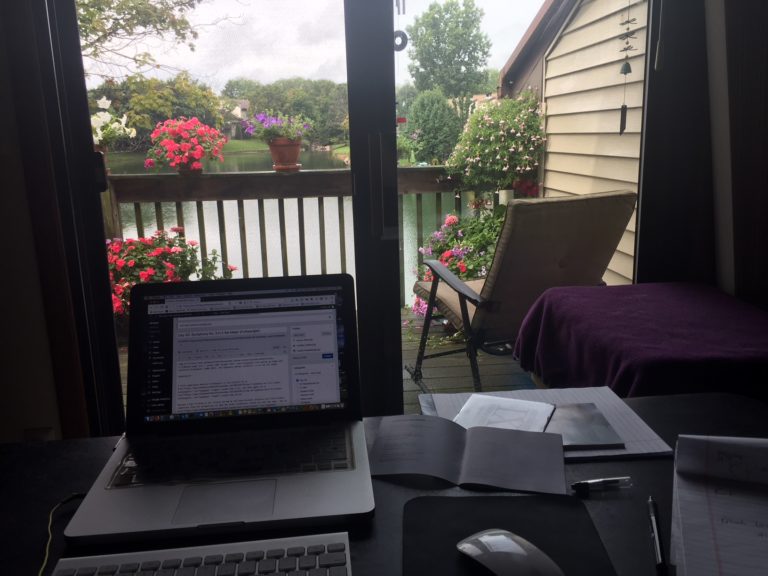

Speaking of which, my office this morning would have been outside on the deck surrounded by lovely flowers in pots and a nice view of the turtles, fish, herons, and ducks on the lake.

As it is, my office while I listen to Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3 in E flat Major is inside, viewing the outside. We just had thunderstorms roll through. And since my Mama didn’t raise no fool, I stayed indoors during the downpour. No worries, though.

I’m only one step removed from the beauty.

Plus, I may set up shop out there again in a few minutes since the skies no longer threaten.

At least, they don’t for the moment. One can never tell living in Michigan.

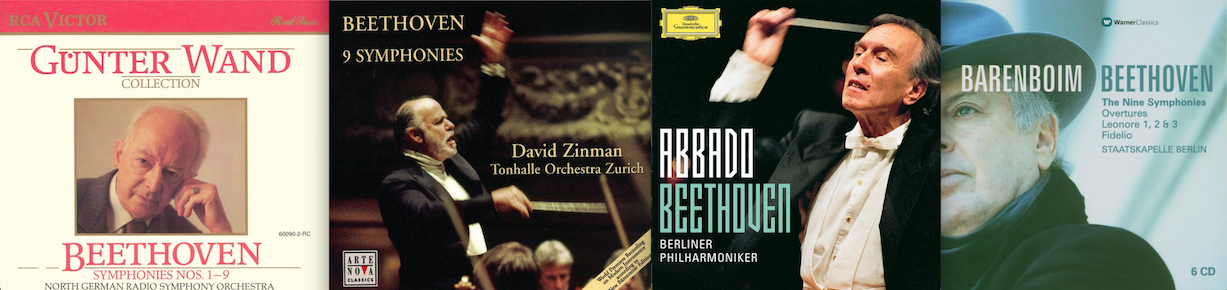

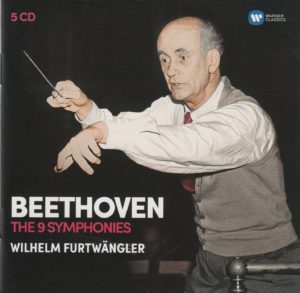

I first experienced Maestro Furtwangler (1886-1954, “…widely regarded as one of the greatest symphonic and operatic conductors of the 20th century,” according to his bio on Wikipedia) in this project on Day 7, and then again on Day 25.

Because I had listened to the Furtwangler during my two-step Bruckner projects (all nine primary symphonies from the perspective of some two dozen conductors, broken up into two legs – see My Year-Long Project), I didn’t hesitate to add him to this Beethoven project.

I knew I was in for a treat this time around because of two things in addition to Furtwangler himself: The Wiener PhilharmonikerWarner Classics. Both are highly regarded in the world of Classical music.

So, with all that going for it, how does Beethoven’s Third fare?

Quite well, actually.

But first, the facts…

Beethoven wrote his symphonies in four parts (except for the Sixth, which is in five). The time breakdown of this particular one (Symphony No. 3 in E flat Major), from this particular conductor (Furtwangler, at age 66) and this particular orchestra (Wiener Philharmoniker), at this particular time in history (November 24 & 26-28 1952) on this particular record label (Warner Classics) is as follows:

Beethoven wrote his symphonies in four parts (except for the Sixth, which is in five). The time breakdown of this particular one (Symphony No. 3 in E flat Major), from this particular conductor (Furtwangler, at age 66) and this particular orchestra (Wiener Philharmoniker), at this particular time in history (November 24 & 26-28 1952) on this particular record label (Warner Classics) is as follows:

I. Allegro con brio………………………………………………………………………16:11

II. Marcia funebre: Adagio assai……………………………………………….17:22

III. Scherzo: Allegro vivace – Trio…………………………………………………6:31

IV. Finale: Allegro molto – Poco andante – Presto…………………..12:20

Total running time: 52:24

My Rating:

Recording quality: 4 (hardly any tape hiss; all instruments clear and bright)

Overall musicianship: 4 (a spirited performance)

CD liner notes: 4 (essays on Furtwangler written in English, German, and French, however historical details missing or hard to find: Where was this recorded? When? What orchestra? That information is in small print on the back of the CD sleeves)

How does this make me feel: 4 (a true historical gem)

I knew I’d enjoy this performance from the opening two chords.

The first movement features many of my favorite sounds and instruments: French horn, flute, pizzicato, and dynamic, full-on orchestration – all within just the 9:20-10:30 mark!

The only complaint I have is that this performance, at 52:24, goes on a little long. That’s particularly noticeable in the 17-minute second movement. That may account for what sounds like a very speedy Movement III (Scherzo) to get the blood pumping again.

From the well-written liner notes by Richard Osborne,

Written in a time of war, in the wake of Beethoven’s recognition of his deafness and his rejection of suicide as a response to it, the Eroica Symphony (1803) is a crucial work in the Beethoven canon. Even nowadays, when we hear the opening bars of the symphony, we should (and in Furtwangler’s lofty, purposeful, uplifting reading we instinctively do) sense that nothing like this had been heard before.

It is music on an epic scale.

Indeed it is.

The Finale, especially, feels epic. Lots of terrific pizzicato strings, passages of triumph and verve, and an overall atmosphere of victory, perhaps tinged with a little melancholy, leading to the dizzying, flamboyant greatness of the final bars.

Of Furtwangler himself, his “Conducting Style” bio on Wikipedia provides many keen and interesting insights, including:

Furtwängler’s recordings are characterized by an “extraordinary sound wealth”, special emphasis being placed on cellos, double basses, percussion and woodwind instruments. According to Furtwängler, he learned how to obtain this kind of sound from Arthur Nikisch. This richness of sound is partly due to his “vague” beat, often called a “fluid beat”. This fluid beat created slight gaps between the sounds made by the musicians, allowing listeners to distinguish all the instruments in the orchestra, even in tutti sections.

Overall, this is a fine historical performance, lovingly remastered and offered in this 9-Sympohony box set by Warner Classics.

I grok. I’ll give it a “Huzzah!” rating.