My office today is the balcony, sans flowers and pots, I not only have a great view, but a very find lunch to boot: a ginger-turmeric kombucha, a turkey wrap sandwich, and a Jonagold apple that we picked ourselves a week or so ago.

Classical music and a delicious lunch. What could be better?

Not much.

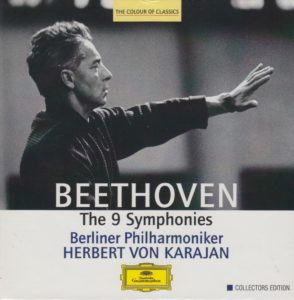

So I munch and listen to Austrian conductor Herbert von Karajan (1908-1989), The Berliner Philharmoniker, and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 in C minor.

Before I started this project, I did my research and bought the two highest-regarded CD box sets from Maestro Karajan, the 1963 cycle and the 1977 cycle…and then I worried that I’d get sucked into the Cult of Karajan, or suffer from Karajan Worship Syndrome.

So many lovers of classical music speak of Herbert von Karajan in hushed tones, as if he’s a deity and we’re merely those he allows to share his world.

I was always on my guard when I listened to Maestro Karahan the four previous times in this project, which was on…

Day 10. Rating: “Huzzah!”

Day 10. Rating: “Huzzah!”

Day 28. Rating: “Huzzah!”

Day 46. Rating: “Huzzah!”

Day 64. Rating: “Huzzah!”

What will today bring? And will the rain begin before I’m done with my lunch and my blog post?

Time will tell!

But first, the liner notes for Symphony No. 5 (written by Richard Osborne) will tell:

The transition from scherzo to finale in Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is one of the tautest and truest of all musical transformations. Yet, as with so much in Beethoven, it was a hard-won victory. Transition is, in every sense, a critical moment, whether one sees it as an enactment of the revolutionary age’s transcendent spirit; or as Beethoven’s own personal ascent from within, the moment in which the composer – increasingly deaf and increasingly isolated – moves from the gloom of the mind’s inner landscape to greet with joy the public world; or, simply, as a wonderful appropriation of the force of minor and major tonality.

To that, I’m tempted to quote Sigmund Freud, “Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.”

Maybe we overanalyze music. Maybe it’s just beautiful and powerful because it’s beautiful and powerful.

However, I do agree with this end to the essay on Beethoven’s Fifth:

Herbon von Karajan made his London debut with the Philharmonia Orchestra in 1948 in a concert which included the C minor Symphony. It is a work he has always conducted with thrilling directness and unforced splendour, the music’s formidable interpretive difficulties squarely faced and brilliantly resolved with no recourse to spurious “traditions.” This celebrated Berlin recording soon proved to be one of the outstanding recordings of its time. Played with consummate skill by the Berlin Philharmonic, it moves from the outset like a sped arrow from the bowstring, majestic, ineffably certain of aim.

Amen.

Beethoven wrote his symphonies in four parts (except for the Sixth, which is in five). The time breakdown of this particular one (Symphony No. 5 in C minor), from this particular conductor (Karajan, at age 54) and this particular orchestra (Berliner Philharmoniker), at this particular time in history (March, 1962) on this particular record label (Deutsche Grammophon) is as follows:

Beethoven wrote his symphonies in four parts (except for the Sixth, which is in five). The time breakdown of this particular one (Symphony No. 5 in C minor), from this particular conductor (Karajan, at age 54) and this particular orchestra (Berliner Philharmoniker), at this particular time in history (March, 1962) on this particular record label (Deutsche Grammophon) is as follows:

I. Allegro con brio (C minor)………………………………………………………7:19

II. Andante con moto (A♭ major)…………………………………………..10:05

III. Scherzo: Allegro (C minor)……………………………………………………4:55

IV. Allegro (C major)………………………………………………………………..9:07

Total running time: 31:26

My Rating:

Recording quality: 3 (noticeable tape hiss throughout; a decent recording despite its 50+-years age, although it seemed to favor the horns too much; otherwise, typical DG-label quality)

Overall musicianship: 5

CD liner notes: 5 (Nice, thick 54-page booklet with lengthy essays by Richard Osborne about each symphony, translated into English, German, and French, and all pertinent technical info)

How does this make me feel: 5 (“Meh!”)

I hated Movement I. It was at that too-fast tempo. It flew by like Morse Code. Or like someone challenged the orchestra to play it as fast as they could.

Most of the symphony seemed too fast for my tastes.

What it felt like was that Maestro Karajan went for kinetic energy, rather than faithfulness to the depth of what Beethoven wrote. In part, that worked. I was digging the breakneck pace of Movement I. But I wasn’t liking that it didn’t feel right.

My favorite movement (III, Scherzo) sounded okay. But not like Blomstedt’s did on Day 76, or Furtwangler’s did on Day 79.

Don’t get me wrong. There is an energy to this recording that is contagious. Plus, there’s that whole historicity thing. This is an historic recording because it’s Herbert von Karajan and…

Wait a minute. See? There it is.

I almost fell into the clutches of the Cult of Karajan.

I almost justified a performance I thought was lacking simply because it’s Herbert von Karajan.

Shame on me!

I’m going to rate this performance a “”Meh!”

I didn’t like the first movement, and I wasn’t thrilled with the following three.

So, there.