This morning, my listening post has actually been three places – this, a local bagel shop, then a local car dealership to swap my snow tires with my regular tires, and now…my actual office.

Yes, I’ve had a hectic morning.

And that’s okay.

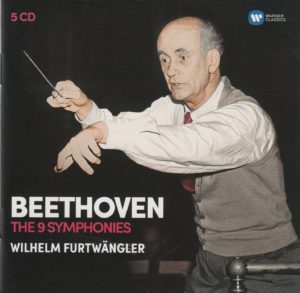

Because, in each place, I listened to German conductor Wilhelm Furtwangler (1886-1954), the Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra (now known as the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra), and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 in F major.

I’ve encountered Maestro Furtwangler six times previously, on…

I’ve encountered Maestro Furtwangler six times previously, on…

Day 7. Rating: Almost “Huzzah!”

Day 25. Rating: “Meh!”

Day 43. Rating: “Huzzah!”

Day 61. Rating: “Meh!”

Day 79. Rating: “Huzzah!”

Day 97. Rating: “Meh!”

I realize Furtwangler is a legend. But, so far, his performances have been hit and miss with me. I realize that’s purely subjective. My opinion isn’t worth a hill of beans. I’m no musicologist. I’m just a guy who loves music. So, please, take what I write with a grain of salt.

Still, I wonder why every other Furtwangler performance is “Meh!” with me?

That makes me wonder what today will bring.

And I’ll know momentarily.

First, though, there’s this from the well-written liner notes by Richard Osborne,

Not far behind the Fifth in frequency of performance by Furtwangler was Beethoven’s Seventh. Occasionally, he would programme the Seventh alongside its serene antitype, the Violence Concerto, or, more often, pit it against the Eighth Symphony if he was in the mood to experience what Neville Cardus once called ‘the laughter of the belly of the universe’. Otherwise, he was reluctant to ‘mix’ the Seventh with other Beethoven. And rightly so: its uniqueness is all.

And then there’s this from the meticulously detailed (and essential if you’re a fan of Maestro Furtwangler) book The Furtwangler Record by John Ardoin:

And then there’s this from the meticulously detailed (and essential if you’re a fan of Maestro Furtwangler) book The Furtwangler Record by John Ardoin:

There is evidence that Beethoven was of two minds about the tempos of the highly original second movement of the Seventh, vacillating between the published indication of allegretto and a tempo closer to an andante. Furtwangler opts for the latter, instinctively aware that there is nothing light in character about this quasi-funeral march. Yet while playing the music with seriousness, he gives it a quick attitude that keeps it alive, and nonharmonic notes here, as throughout his performances of Beethoven, are on the beat, which adds immeasurably to the harmonic interest and flow.

Beethoven wrote his symphonies in four parts (except for the Sixth, which is in five). The time breakdown of this particular one (Symphony No. 7 in A major), from this particular conductor (Furtwangler, at age 64) and this particular orchestra (the Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra – now known as the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra)), at this particular time in history (January 18-19, 1950) on this particular record label (Warner Classics) is as follows:

Beethoven wrote his symphonies in four parts (except for the Sixth, which is in five). The time breakdown of this particular one (Symphony No. 7 in A major), from this particular conductor (Furtwangler, at age 64) and this particular orchestra (the Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra – now known as the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra)), at this particular time in history (January 18-19, 1950) on this particular record label (Warner Classics) is as follows:

I. Poco sostenuto – Vivace……………………………..13:07

II. Allegretto………………………………………………………10:19

III. Presto – Assai meno presto (trio)……………….8:40

IV. Allegro con brio…………………………………………..6:55

Total running time: 38:21

My Rating:

Recording quality: 3 (heavy tape hiss, a few ambient noises, sounds flat and mono – both of which are not unexpected given the age of this recording – but is in full possession of the top end)

Overall musicianship: 5 (gets better with each listen)

CD liner notes: 4 (essays on Furtwangler written in English, German, and French, however historical details missing or hard to find: Where was this recorded? When? What orchestra? That information is in small print on the back of the CD sleeves)

How does this make me feel: 4 (“Huzzah!”)

The first time I heard this performance, I was underwhelmed. In fact, I thought, “This is going to be a sleepy performance, isn’t it?”

But then, after about four listens through its entirety, during the middle of the beloved Movement II, it clicked.

I was deeply moved, carried away by the heartbreaking nature of the second movement.

And then everything else opened up.

The power of that second movement cannot be overstated. It is everything to me, the fulcrum upon which the entire symphony balances.

Furtwangler knocked it out of the park with this movement and, thus, saved the entire performance.

This is a spirited, muscular performance of Beethoven’s Seventh. The recording isn’t too bad, despite it being recorded 68 years ago. I’ve heard worse. I’ve heard better. It’s not bad.

What I discovered listening to it in three different places this morning is that it requires repeated listening to crack it up, to make a competent decision. Once its secrets are revealed, it becomes a very powerful performance, indeed.

I can wholeheartedly recommend Maestro Furtwangler’s performance.

“Huzzah!”