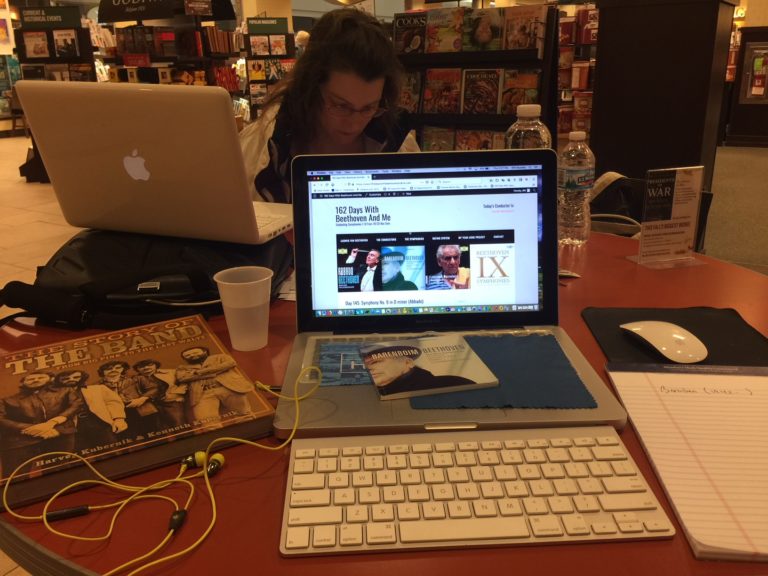

My listening post today is a local Barnes & Noble bookstore.

For being 2pm, this place is surprisingly busy.

We have a couple of hours before we go next door to the theater to watch the documentary Maria By Callas, a documentary about (arguably) the most famous female opera singer of the past 100 years.

I’ve encountered Maestro Barenboim eight times previous to this afternoon, on…

Day 2. Rating: None.

Day 2. Rating: None.

Day 20. Rating: “Huzzah!”

Day 38. Rating: “Almost ‘Huzzah!'”

Day 56. Rating: “Almost ‘Huzzah!'”

Day 75. Rating: “Huzzah!”

Day 92. Rating: “Huzzah!”

Day 110. Rating: “Meh!”

Day 128. Rating: “Huzzah!”

That’s quite good, actually. One “None” rating, one “Meh!”, four “Huzzah!” ratings, and two “Almost ‘Huzzah!'”

Apparently, my rating skills weren’t very sharp when it comes to Maestro Barenboim. I have no idea why. It’s not laziness, I assure you.

I’m eager to see what today brings.

But first, a brief excerpt from Daniel Barenboim’s book Everything Is Connected: The Power Of Music (pages 22 and 23):

In the last movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, the music comes to a complete stop on a sustained, fortissimo chord at the text, ‘Und der Cherub stebt vor Gott‘ (and the cherub stands before God). The music modulates from A major to F major on the last repetition of the words ‘vor Gott’, which are repeated independently of the rest of the sentence. What happens next could never have been predicted: when the music picks up again it is in a new key, a new tempo, a new meter and a new vein, leading the movement in an entirely different direction: just as, in a sense, the world was lead in a different direction after 9 November 1989, or 11 September 2001. Music teaches us that we have to accept the inevitability of an incident that change the course of events irrevocably. Although one can have either an irrational sense of optimism or an irrational sense of pessimism following a great catastrophe, the ebb and flow of life, like the ebb and flow of music, are undeniable.

And, of course, this from the superb liner notes (written by Robin Golding), pages 20 and 21:

The composer’s magnum opus and the culmination of the medium: with his Ninth Symphony, Beethoven created a work that is altogether unique in its form and orchestral resources, to say nothing of its significance for the whole of the later history of music and its importance in terms of tolday’s concert life. When we speak of “the Ninth”, it is clear we mean Beethoven’s…for a long time, later composers felt overshadowed by Beethoven and turned in other directions or, like Brahms, hesitated for decades before writing their own first symphonies

Okay. Now on to the the nuts and bolts of today’s post.

Hang on.

One more tidbit.

Does anyone remember the Huntley-Brinkley Report? The closing theme used a portion of the second movement of Beethoven’s Ninth. There’s a link on this web site. I still remember that theme, and was surprised when I first heard Beethoven’s Ninth. It was the Huntley-Brinkley theme song!

Now, on to the nitty-gritty.

Beethoven wrote his symphonies in four parts (except for the Sixth, which is in five). The time breakdown of this particular one (Symphony No. 9 in D minor), from this particular conductor (Barenboim, at age 57) and this particular orchestra (Staatskapelle Berlin), at this particular time in history (May – July 1999) on this particular record label (Warner Classics) is as follows:

Beethoven wrote his symphonies in four parts (except for the Sixth, which is in five). The time breakdown of this particular one (Symphony No. 9 in D minor), from this particular conductor (Barenboim, at age 57) and this particular orchestra (Staatskapelle Berlin), at this particular time in history (May – July 1999) on this particular record label (Warner Classics) is as follows:

I. Allegro ma non troppo, un poco maestoso………………….17:35

II. Molto vivace…………………………………………15:15

III. Adagio molto e cantabile……………………………..17:56

IV. Finale……………………………………………..25:38

Total running time: 76:40

My Rating:

Recording quality: 3 (an okay recording; however, it sounds a trifle muffled, like some of the top end is missing, or the music is too packed into the mid range, the violins sound subdued; in fact, all of the instruments sound like I’m listening to them from another room)

Overall musicianship: 4 (competent, slow of tempo – these are very long movements)

CD liner notes: 5 (a nice, meaty booklet; lots of info in several languages)

How does this make me feel: 4 (“Meh!”)

This is an extremely difficult symphony to rate. It’s massive. In fact, Movement IV is as long as the previous symphony, Beethoven’s Eighth.

What makes it harder to write about, discern, is that it has few passages of memorable melody, with the exception of the theme from the Huntley-Brinkley Report, which uses a portion of Movement II, and the “Ode to Joy,” which is in Movement IV. That’s an extremely recognizable melody.

So I’m clearly not talking about “Ode to Joy.” It’s the other 50 minutes of the symphony that don’t have a “hook” for me to hang my hat on.

That’s not to say this is a crappy symphony. On the contrary, I can easily hear how complex and majestic it is.

For example, Movement I is a wonderful, wonderful movement. It begins with a mood somewhat like the sonic equivalent of the rising sun. Lots of nice melody in this piece of music (portions of the melody reappear in the beginning of Movement IV).

One thing I have to say is that this is a long interpretation, which might mean Maestro Barenboim retarded the tempo a bit. Every movement is longer than Claudio Abbado’s. The total running order for this performance is an hour and 16 minutes.

That’s a long time, ladies and germs.

The choral part is fine. The male voice is powerful and clear.

In fact, the entire operatic (sung) part is the most powerful of this performance. It’s big and bold, with lots of dynamics, and well recorded. Given what I’m hearing in the choral part, it sounds like Maestro Barenboim has an affinity with this type of music. It sounds more powerful than the rest of this recording. Or maybe this punchiness of this part of the Finale is totally due to the expertise of chorus master Eberhard Friedrich.

I dunno.

Maybe I’m just not diggin’ the Ninth the way I was some of Beethoven’s other symphonies.

Or maybe this is too long and under-delivered.

I’m going to have to rate this “Meh!”

I’m sorry, Maestro Barenboim.