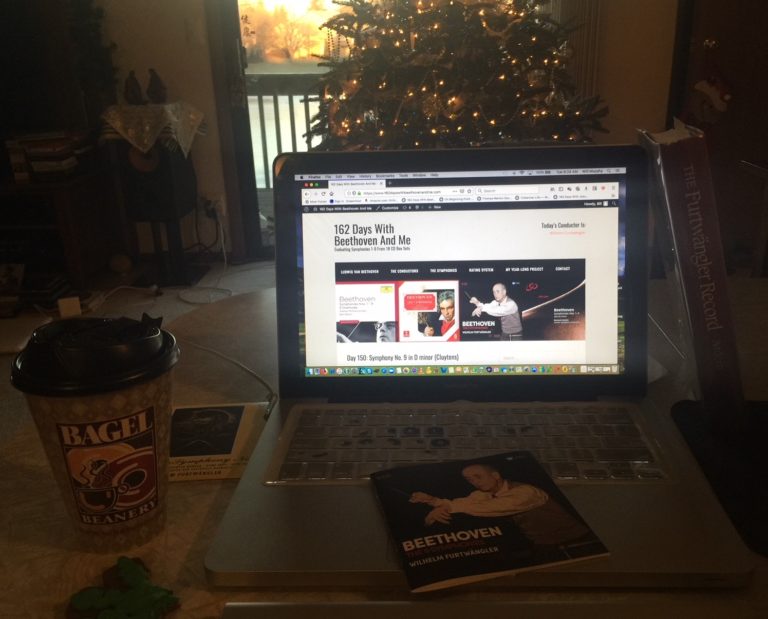

My listening post this morning is with a cup of coffee from Bagel Beanery to my left, just above a gingerbread cookie (which my wife bakes to perfection and is known far and wide for her skill), a twinkling Christmas tree before me, and a copy of John Ardoin’s indispensable book The Furtwangler Record to my right. (No self-respecting fan of Wilhelm Furtwangler should be without Ardoin’s book.)

From Ardoin’s book, pages 142, 143:

Clearly, in living with and restudying this epic work, Furtwangler saw the opening three movements of the Ninth (beyond any consideration as pure music) as being colored and conditioned by the finale. He made one feel that from within the misty void which opens the symphony, there is struck a spark of Promethean life which soon blazes in violent, flashing rhythms and singeing sounds. No wonder Furtwangler had so little interest in calibrating to the last sixteenth note those opening string triplets. Here, it was not the word, but the sentence and the paragraph that riveted his imagination and shaped his approach. This opening allegro, ma non troppo was to him – as it becomes to us – a life source, as inexplicable as the elements themselves.

In the background at my listening post – mimicking the low sound of music in a restaurant – are the first four albums from The James Gang, and an early album from Hot Tuna.

I’ve been eager to hear this symphony performed by Maestro Furtwangler since it arose in rotation – especially since I read about his performance of it at Hitler’s birthday, and what a raucous performance that was. I tracked down that performance and downloaded it from the French web site Pristine Classical.

I discovered this “terrifying” performance from the article on Beethoven’s Ninth in The Guardian, in which the author wrote:

Five key recordingsWilhelm Furtwängler/Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra: maybe the most terrifying music-making that I know; a performance for Hitler’s birthday in 1942 that seethes with a daemonic intensity. The end sounds more like a scream of pain rather than a shout of joy.

How could I pass up the chance to hear that?

I couldn’t.

Perhaps you can’t, either.

Click on the link from Pristine Classical and listen for yourself.

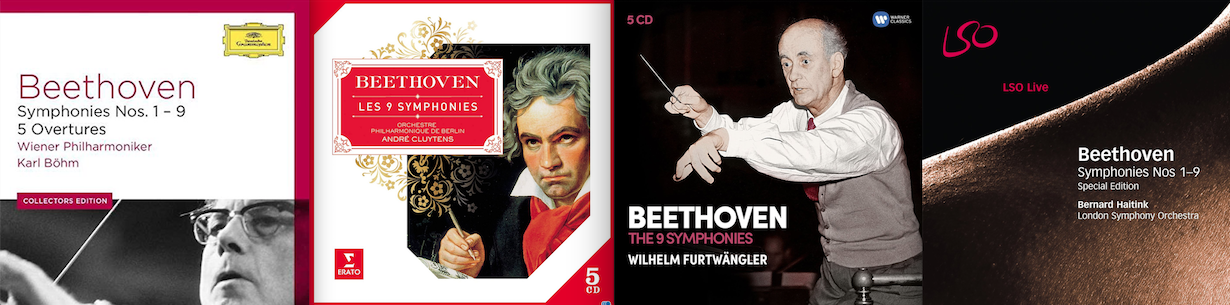

I encountered Maestro Furtwangler eight times previous to this morning, on…

Day 7. Rating: Almost “Huzzah!”

Day 7. Rating: Almost “Huzzah!”

Day 25. Rating: “Meh!”

Day 43. Rating: “Huzzah!”

Day 61. Rating: “Meh!”

Day 79. Rating: “Huzzah!”

Day 97. Rating: “Meh!”

Day 115. Rating: “Huzzah!”

Day 133. Rating: “Meh!”

Four “Meh!’ and nearly four “Huzzah!” ratings.

Not the best record in my Beethoven project. But not the worst, either.

I seriously doubt today’s performance will be “terrifying” like the 1942 Hitler’s B-Day installment. But, given Maestro Furtwangler’s record, it may be. But not for the same reasons.

I’ll know in about an hour.

Beethoven wrote his symphonies in four parts (except for the Sixth, which is in five). The time breakdown of this particular one (Symphony No. 9 in D minor), from this particular conductor (Furtwangler, at age 65) and this particular orchestra (the Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra – now known as the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra), at this particular time in history (July 29, 1951) on this particular record label (Warner Classics) is as follows:

Beethoven wrote his symphonies in four parts (except for the Sixth, which is in five). The time breakdown of this particular one (Symphony No. 9 in D minor), from this particular conductor (Furtwangler, at age 65) and this particular orchestra (the Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra – now known as the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra), at this particular time in history (July 29, 1951) on this particular record label (Warner Classics) is as follows:

I. Allegro ma non troppo, un poco maestoso………………….18:02

II. Molto vivace………………………………………..12:05

III. Adagio molto e cantabile……………………………..19:40

IV. Finale……………………………………………..25:13

Total running time: 75:04

Those numbers give me serious pause.

Seventy-five minutes!

This could be an arduous listen if it’s not riveting.

But I’m going to take one for the team and and give it a go.

But first, this from the the superb liner notes by Richard Osborne:

In an essay published in 1964, the critic Neville Cardus wrote: ‘Furtwangler’s unfolding of the Ninth Symphony was, in my opinion, the biggest scaled – most inward-thinking in the slow movement, cosmic in the first – that I have ever heard.

My Rating:

Recording quality: 4 (moderate tape hiss, sounds like a mono recording, somewhat flat)

Overall musicianship: 4 (magical, smart, passionate)

CD liner notes: 4 (essays on Furtwangler written in English, German, and French, however historical details missing or hard to find: Where was this recorded? When? What orchestra? That information is in small print on the back of the CD sleeves)

How does this make me feel: 5 (“Huzzah!”)

I realized going into this recording that its sound was likely going to be rough and that I couildn’t judge it based on that, alone, or allow much of my opinion of it to color my overall review. After all, 1951 was nearly 70 years ago. I can’t expect pristine sound with all the stereo and depth and breadth.

So I set aside the sound quality of this recording and just listened.

And I found that when I did that, the magic and mystery and brilliance jumped out at me.

But I have to arrive at that by listening between the notes. I have to allow the entire symphony to wash over me, take it all in as a whole, not picking out instruments that should be clearer or crisper, not thinking the entire recording lacks breadth and, therefore, the 1-2 punch that performances by Leonard Bernstein or Franz Konwitschny possess.

Even setting aside the less-than-stellar sound quality, I have to admit Movement I dragged a bit. It wasn’t mysterious and mystical, beckoning me in. It seemed more plodding that pulsating with energy.

Movement II saved the recording, though. It did pulsate with energy.

Movement III is a brilliant, sorrowful composition that tugs at my heartstrings.

Movement IV is dynamic. And extremely powerful, especially when the “Ode to Joy” melody kicks in around the 3:05 mark, beginning slowly, quietly, until it explodes in full orchestra around the 5:40 mark.

Movement IV steals the show. It’s a tour-de-force of two artists (Furtwangler and Beethoven) at the top of their game.

Now, granted, I’m purposely not harping on the sound quality, not even during the 10:30 mark when it sounds like every voice in Germany was singing at the same time. It’s a powerful, humbling moment. Big doesn’t even begin to describe it.

But it could have been mind-blowing, heart-stopping, and/or life-changing if it had been recorded in, say, 2001 or even 1986.

Still, this is remarkable performance.

Especially during the last two minutes when the tempo ramps up to breakneck, and every voice and instrument seems to be playing at once, as fast as they can. The sound is massive. The excitement level is off the charts. I’ve never heard anything like it.

The roar of the audience at the end of the last note was equally as powerful.

“Huzzah!”